Criticism of

Claude Monet's “Houseboat”

& Other Works

Lincoln University

Kyle Wanamaker

Intro to Art

Art 102, Fall 2008

Criticism

of Claude Monet’s “Houseboat” & Other Works

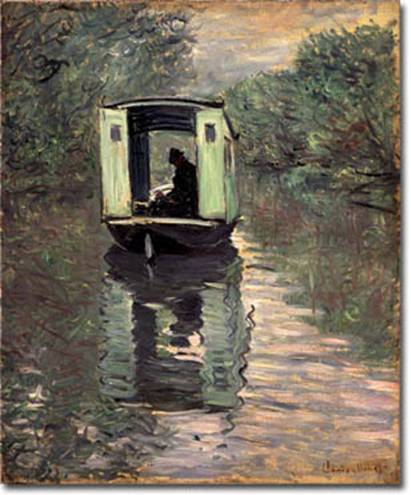

Claude Monet’s 1876 work entitled “Houseboat” depicts

a single man inside of a small boat on a river bordered with trees. While the

Barnes Foundation translates the work as “Houseboat”, a literal translation

from the French title “Bateau Atelier” reveals the title to be “Boat Studio”

(Wordreference.com, 2005).

“Houseboat” is an oil-on-canvas painting measuring

approximately 29 in by 24 in (h x w). In it, we see a small, wide bottomed boat

with a rectangular room atop a narrow river. The river extends from the bottom

of the canvas and to the horizon where it is balanced with a blue and orange

sky. The small boat hides the vanishing point of the work.

The river is beset on both sides with trees that

encroach over the banks and cast long shadows onto the waters around the boat.

The dividing line between water and riverbank vegetation is subtle with the

trees’ reflection resembling a muted version of the curling brush strokes

dominated by green, brown, and brownish-red hues. Monet appears to have painted

the left bank with hasty brushstrokes that at times seem out of control. He

blends the blues of the sky with the trees on the left bank, which does not

also happen to the same degree with the right-hand bank.

As the trees from both sides lean over the river, they

leave a stretch of sky exposed that mirrors and balances the path of the river.

The sky is painted with less obvious strokes than the rest of the work, and

changes in color from bluish white to orange as the eye progresses up the

canvas, away from the horizon line. Inside the boat, a man sits with his back

to the right-hand wall, his head down, as if in concentration, while a hat and

overcoat don his person.

“Houseboat” exhibits a large degree of vertical

symmetry due to the reflection of imagery above the horizon appearing in the

water below. The work balances the gentle curvature of the waves and trees with

the stark lines of the manmade craft at the center. The pale, confined whitish

sides of the shack atop the boat contrast with the flowing mass of naturalistic

colors found everywhere else. Inside the boat appears very dark and solemn,

whereas the exterior of the boat appears frenzied, but not particularly joyous.

The usage of dark colors without a defined point of

lighting suggests the day is overcast, and lends a melancholy mood. This is

exacerbated by the slumping figure within the boat. The sole usage of warm

color is a small trace of orange in the sky and a more miniscule amount

reflected in the water.

Despite the quick brushstrokes used throughout the

work, there is a very strong sense of geometrical proportion. The lines of

where the sky meets the trees along each bank form an acute triangle. Where the

bank meets the water, and the reflection of the sky onto the water form two

concentric pyramids. All of the triangles direct the viewer to the occupant

within the floating studio. Furthermore, the boat itself exists in geometric

proportion. The hull and roof could extent to create a gentle ellipse in which

the rectangular walls of the studio would be circumscribed. The rectangular

walls themselves are repeated in the shape of the door that allows us to see

the sole occupant. The formation of triangles pointing to circle to rectangle

within a rectangle firmly puts focus on the individual in the boat, an

individual who himself resembles a pyramid, and even extends the reflection of

the sky in the water. However, the vanishing lines of the piece do not all

actually appear to be within the man.

Some of vanishing lines actually appear to converge

slightly to the left of the main subject. The subject of strokes around the man

is less obvious than those of the larger work; it is not obvious whether the

viewer is seeing water, or sky, or flora and fauna. The strokes simply encircle

the subject’s head, almost resembling the halo seen around religious figures

works from the Middle Ages. Although no religious imagery appears, the figure

does seem to have a solemn reverence as if he is meditating on something.

The convergence of pyramids and the stability and

triangular shape of the central figure amidst the tempest and movement of all

other forms in the work is remiscent of Da Vinci’s “The Last Supper”. In fact,

another common is the main figure in front of an opening through which we see a

landscape. However, few, if any, of Monet’s major works were of any religious

significance. Yet Monet could have been feeling spiritual reverence. Levine

asserts that the figure is Monet, and that the work is “Narcissus-like” (pp131,

1995). In 1876, the same year as “Houseboat” his wife became ill from

tuberculosis, and Monet began an affair with Mme. Alice Hoschede (Strieter,

1999). Any man willing to take on a mistress with an ailing wife and a

burgeoning family with infant children must take a sense of pride in himself.

Monet was probably no exception.

Monet was known for his studies of the same scene at

different times during the day, and different times during the year. He was

interested in the different lighting characteristics, and also with capturing

the movement of water. His many studies of water Lillies from his later years

at Giverny serve as evidence of this. However the boat studio predated his move

to Giverny by 6 years. In fact, his boat was purchased shortly after his return

to France from the Netherlands in December 1871 (Mancoff, 2007). Monet used his

studio boat to gain a different perspective of the bank and the water for his

paintings (ibid). His studio boat is the subject of his 1874 work entitled “The

Studio Boat” housed in the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands.

“The Studio Boat” depicts the same craft as in

“Houseboat” moored in what appears to be a large river. Both of these works

were early in his state of impressionism. Monet debuted the “impressionist”

style in 1874 with his 1872 work entitled “Impression, Sunrise”. Monet

continued with impressionism until his death, and in later years progressed to

the studies of the same landscape as mentioned above.

Yet despite both works containing some similarities,

“The Studio Boat” does not appear to share many of the aesthetics of

“Houseboat”. There is no person in the work, the usage of geometrical shapes is

non obvious, and although the boat is clearly the focus of the piece, it does

not dominate and the viewers attention in the same manner as “Houseboat”. “The

Studio Boat” appears to be a study of the trees reflected in the water much

more so than of the boat. The boat is rigid, and its obtuse angle to the viewer

seems awkward—the eye is drawn to the sweeping strokes of the trees and their

reflection rather than to the pale boat. The work lacks a personal quality and

intimacy that "Houseboat" vividly portrays.

Both “The Studio Boat” and “Houseboat” can be compared

to Monet;s later works, many of which were series of works on the same subject.

His gardens and pond at Giverny gave him many opportunities for subject matter,

but he did not paint them in his beginning years there (pp 271, Tucker, 1992).

His later paintings at Giverny did show his pond, and Monet is especially known

for his studies of water lilies from late in his career.

Monet's water lily studies consist of over 200 works

which exist in museums around the world. On June 24, 2008 one of the paintings

sold for over $80M at auction. "Le bassin aux nymphéas (1919)" is a

large work of almost 40in by 80in (h x w), depicting Monet's pond, with water

lilies afloat, and the gentle reflection of trees and sky along the water's

surface.

“Le bassin aux nymphéas” reflects a calm peace in the

water which exists in "Houseboat" but not in "The Studio

Boat". The brush strokes are not as obvious as in the earlier works, and

there is much more use of color spread throughout the canvas, rather than

concentrated in certain areas. The use of greens is pervasive, but anticipated

due to the natural subject matter. However, the usage of rich blues and purples

seems to accentuate the otherwise uniformity of the greens.

“Le bassin aux nymphéas” allows the viewer to create

the picturesque scene. The viewer can choose the time of day and the

atmospheric conditions more so that in either of the two boat studies. The

calming sense of peace pervades the work, as the brush strokes are muted, and

show little activity on or in the water. The lily pads are loosely painted,

without definite form, unlike the forms in the earlier works. The pads appear

somewhat dreamlike, floating on the water, yet not distinct from it, as the

blues and greens sneak through the gaps in the circular strokes depicting the

pads.

The variance of color comes from the reds and purples

in the flowers on the pads. To a lesser degree, there is some violet in the

water as it approaches the bottom of the canvas. However there is a lack of

definite lighting and it's hard to tell whether the water is dark because it is

deep, or because of the lighting conditions at the time. These little mysteries

are what make “Le bassin aux nymphéas” interesting to the viewer. There are

some mysteries to “Houseboat” as well, but most of them are concerned with the

man in the boat: What is he doing? What is he thinking? They mysteries of “Le

bassin aux nymphéas” are directed inward; that is, the viewer has to create the

details outside of the canvas, rather than within them.

The viewer's creating of details is what ultimately

makes Monet and impressionism engaging to the viewer. No longer presented with

a realistic image, the viewer must create details--create their own image.

Ultimately, Monet's use of stroke and color creates art that invites the viewer

to be active rather than passive: a great accomplishment indeed.

Houseboat

http://www.barnesfoundation.org/images/the_house_boat.jpg

The

Studio Boat

http://www.mystudios.com/art/impress/monet/monet-studio-boat.jpg

“Le bassin aux nymphéas”

http://talent-talk.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/08_monet_lilies.jpg

Works

Cited

Levine, S. Z. (1995). Monet, Narcissus, and Self-Reflection: The Modernist Myth of the Self.

Retrieved 14 November 2008

from http://books.google.com. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mancoff, D. N. (27 August 2007). Claude Monet

Paintings 1861-1874. Retrieved 15 November 2008 from HowStuffWorks.com:

http://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/claude-monet-paintings-1861-1874.htm

Strieter, T. W. (1999). “Camille Doceaux” in Nineteenth-century European Art: A Topical

Dictionary. West Port, CT: Greenwood

Publishing Group.

Tucker, P. H. (1992). Monet in the '90s: The Series Paintings. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.